This article is an excerpt from my book, Quality First Investing. It is a book I wish I had read 20 years ago myself as a budding investor. It is primarily a practical guidebook to quality investing through in-depth, on-the-ground research.

Patience is a virtue when buying great companies and the secret to making your money grow. High-quality companies are rarely available at cheap valuations, but once in a while, you will be able to buy them at reasonable prices – especially during an economic downturn or a temporary setback. Also, you have to have the patience to ride through the inevitable downswings, to wait for great investments to play out and let the power of compounding do its work. However, the idea that patience is the most essential investor quality is not new and preached by Warren Buffett himself when he says, “Inactivity bordering on sloth is the cornerstone of our investment approach.”

In 1973 Warren Buffett invested more than US$10 million in The Washington Post Company. By the end of 1974, the share price had dropped nearly 25% and it took three years to recover fully. Instead of selling his stake while the price was falling, Buffett went against the herd and continued buying. He knew that the fundamentals of the business were strong and that the stock was cheap. Over time the share price bounced back and the business grew – and so did the underlying business value. Because of stock repurchases, per-share business value increased considerably faster. Today Buffett regards his investment in the Washington Post as one of his best and most profitable ever.

Maintaining a multi-year view by focusing your thoughts on the long-term fundamentals and not expecting instant returns is probably the most important aspect of avoiding short-term noise. It’s critical to resist the pull of action for action’s sake. If Buffett had sold his shares in the Washington Post Company when the price fell, he would have lost money and missed out on the potential for future returns. Similarly, it’s typically better to stay on the sidelines and wait for better opportunities than to commit to owning stocks priced for sub-par returns. The patient investor usually doesn’t have to wait more than a year or two, due to the volatility of the marketplace. In the meantime, building a watchlist of great companies to own at the right price is time well spent.

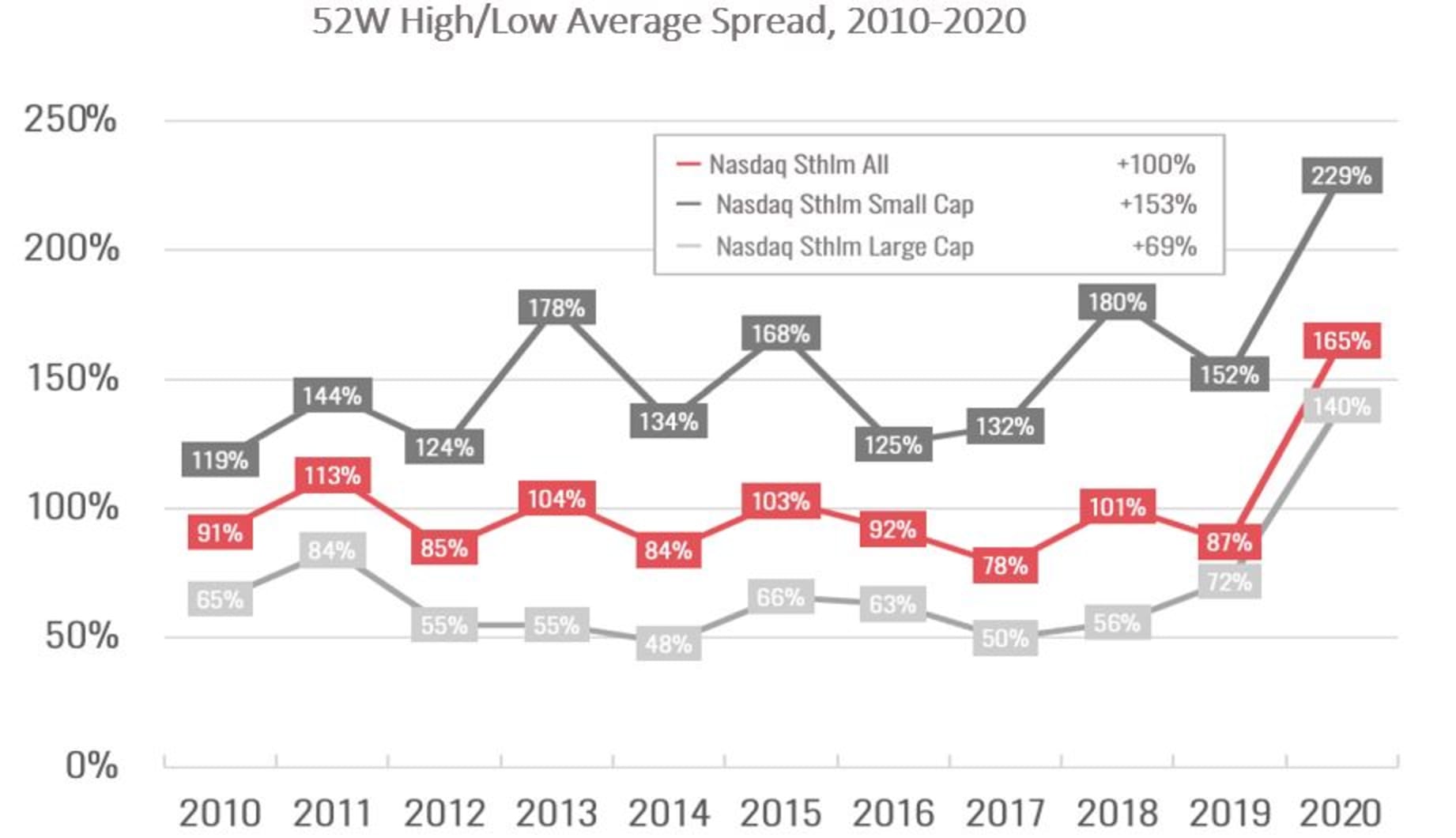

The average share price fluctuates by roughly 100% annually, comparing 52-week low to 52-week high. This assumption is based on the results from a volatility analysis on all stocks traded on Nasdaq Stockholm Exchange for the period 2010-2020, see chart below. Clearly, the average business’s underlying value doesn’t fluctuate this much over a year. Hence, the smart investor takes advantage of short-term market swings by having cash available to invest and waiting for high-quality companies to be attractively priced. However, selling a great company because of a high valuation often involves hoping to buy back at lower prices later on, which is wishful thinking and not a strategy.

Source: Redeye Equity Research and Bloomberg

This quote from the famous value investor Howard Marks is well worth remembering and serves as a fitting conclusion to this section: “When there’s nothing particularly clever to do, the potential pitfall lies in insisting on being clever.”

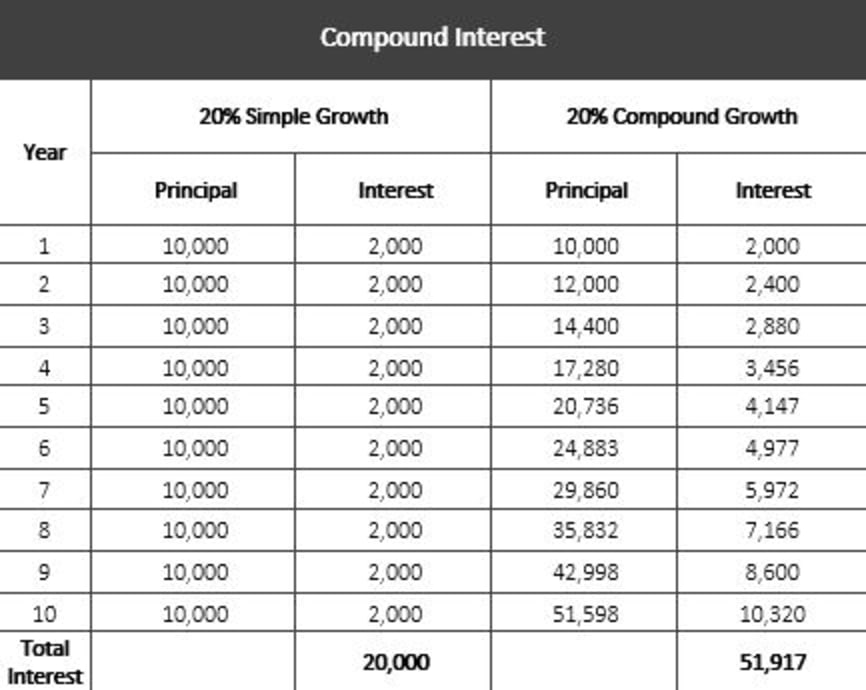

The Beauty of CompoundingAlbert Einstein famously referred to compound interest – that is, the return on incremental capital – as the eighth wonder of the world. He also called it “mankind’s greatest invention because it allows for the reliable, systematic accumulation of wealth.” Although its power is relatively invisible over short periods of time, it is enormous over the long term. Keep in mind that more than 97% of Warren Buffett’s net worth came after his 65th birthday. As noted, much of the secret to successful investing is the compounding of returns over time, as the table ‘Compound Interest’ below illustrates.

Source: Redeye Equity Research

Harnessing the power of compounding will greatly impact your investment returns over time. Yet, people tend to confuse linear returns with the much more powerful exponential effect of compounding, which explains why the latter is often underestimated. After all, understanding that your portfolio can multiply 100 times in 25 years when you compound at 20% annually is simple, but not intuitive. However, patiently sitting through these 25 years earning an annual return of 20% is anything but easy. If you sell in year 20, you will get ‘only’ about 40 times. But if you hold it for just 10 years, you ‘only’ returned five times your money. So patience is required.

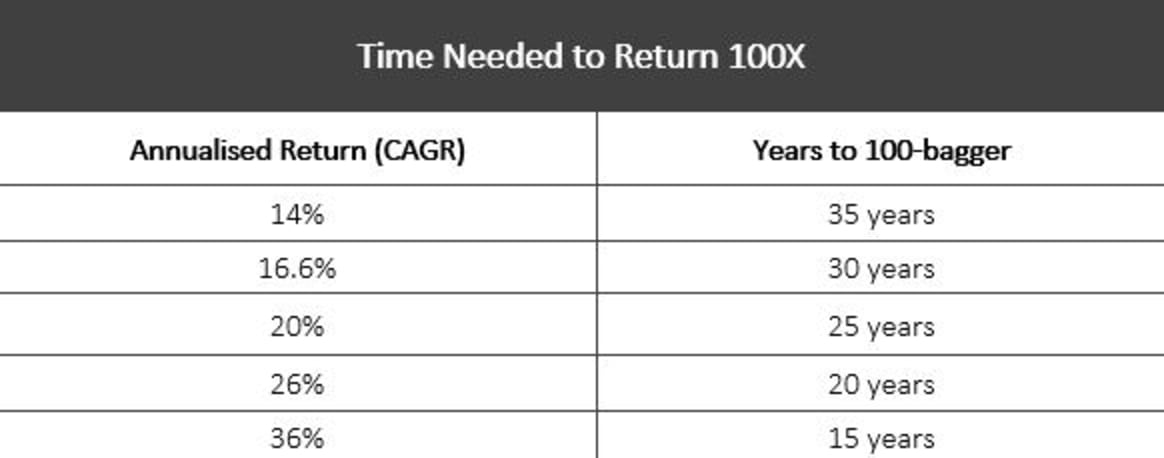

Thomas Phelps, provided a table in his wonderful book, 100 to 1 in the Stock Market, which lists the annual returns and how many years it would take before you get a 100-bagger:

Source: 100 to 1 in the Stock Market, Thomas Phelps, 2015

Another useful tool for assessing the impact of compound interest and the doubling effect is the Rule of 72. The rule says that if you divide an interest rate into 72, it will tell you how many years it will take to double your investment. At 24% interest, a buck would double in 3 years (72 / 24 = 3).

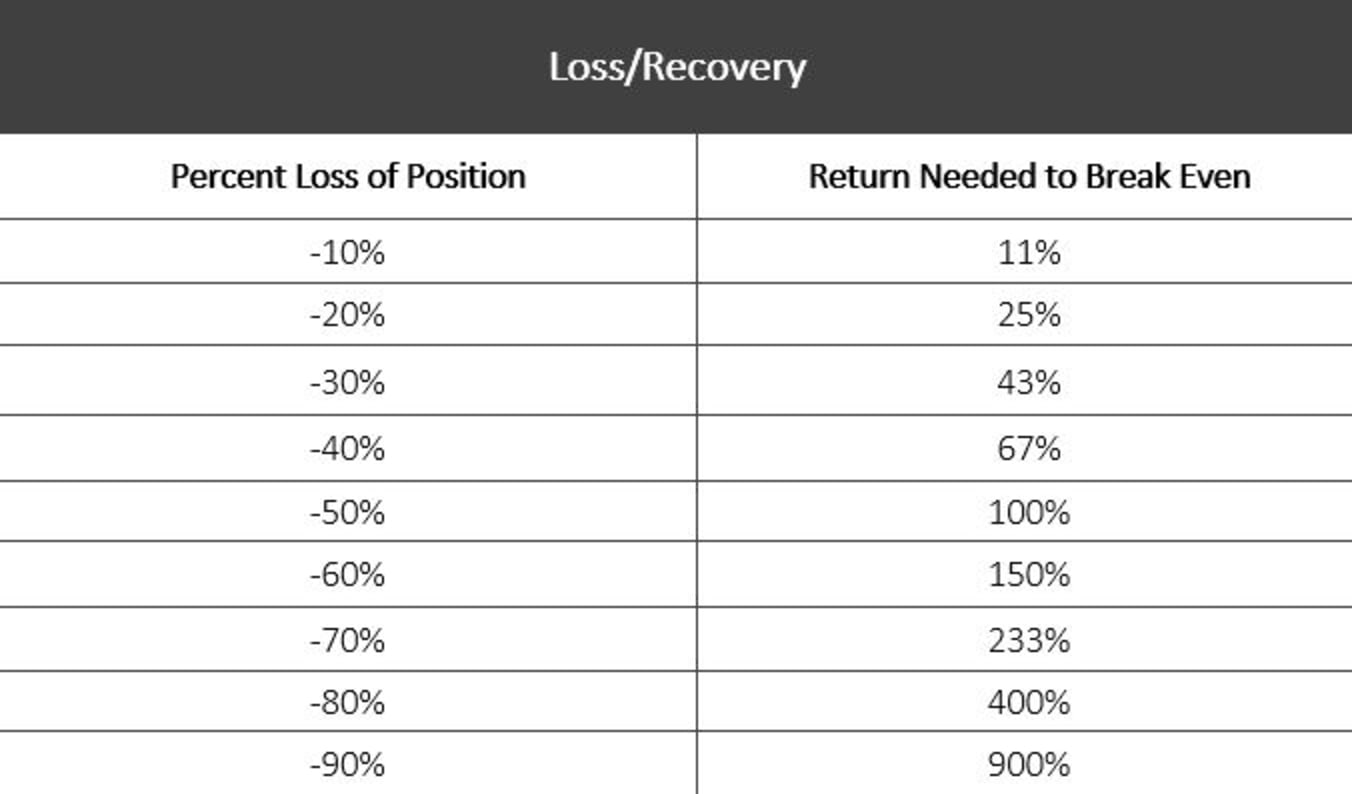

The Ugly Side of CompoundingJust as compounding geometrically increases the value of positive returns, it also exacerbates the impact of negative returns. The bottom line is that it’s very difficult to recover from a large loss or make up for negative-compounding years, to get you back to even. As rewards and penalties for compounding are asymmetrical, what you should be trying to accomplish is to avoid big mistakes.

Winning big in the stock market is all about losing the least amount possible when you’re wrong, not being right all the time. Remember, a seasoned investor who earns 20% for two consecutive years comes out ahead of a newbie investor who earns 100% in a bull year and loses 30% or more in the following year.

There is an old saying; “There are old pilots and there are bold pilots, but there aren’t many old, bold pilots.” The point is that you should always try to put yourself in a position where the likelihood of a big drop is extremely limited. As explained before, staying power counts in the investment world.

The ability to stick around for a long time should be the cornerstone of any investment strategy. That’s why you should avoid leverage (borrowed money) at all costs. Leverage just magnifies outcomes, not adding value. Never forget that any stock you buy, or your whole portfolio, can go down 50% or more on the whims of the market. Leverage could literally destroy in a moment the benefit of many years of investment success.

Also, you should seek to avoid overly leveraged investments and ‘lottery tickets’ – the get-rich-quick stocks – or at least ensure that these make up no more than a small portion of your portfolio. In other words, keep your mistakes small enough so you can survive them; the upside takes care of itself.

The following table illustrates the asymmetrical impact of compounding – the more you lose, the harder it is to get back to even.

Source: Redeye Equity Research

However, interrupting the compounding clock can occur in many ways. Another common mistake is abandoning an investment strategy that has worked reasonably well over the long term but recently had a few bad years. Moving on when things get tough to the hot new thing is likely to leave you worse off. Still, this investment failure is common as most investors have a year-end focus. It is intuitive to feel that the pursuit of the best returns at all times is the best way to maximize wealth. Nonetheless, maximizing annual returns in a given year and maximizing long-term wealth are two different things.

If the average investor is trying to win in the next year, and you trying to win over the next five years, you both have the potential to win. But you are ultimately going to outperform by resisting the urge to ‘swing for the fences’. Successful investing is not about beating the market every time: it’s about beating the market over time.

How to Hold CompoundersAs Charlie Munger says, “the first rule of compounding is to never interrupt it unnecessarily.” The power of compounding can only be achieved by holding a stock for years, if not decades. The mistakes that will impact your performance most when investing in compounders are likely to be decisions to sell too soon (see ‘What Makes a Compounder’, below). One of the most powerful concepts in portfolio management is to let your winners run. This is simple but very difficult to execute.

The bottom line is that you can borrow ideas, but you can’t borrow conviction. You will never hold the compounders long enough to achieve stellar returns if you don’t understand what you own, why you own it, and the value of it. You need deep industry expertise (past work) or recent analysis (current work) and the correct mindset to withstand the pain of extreme paper losses. Keep in mind this is the key reason for doing fundamental research – to forge the courage to hold on to or buy into stocks after they have disconnected from reality on the downside.

Building conviction is what makes investing part-time so difficult and why most retail investors struggle with stock selection. However, this is also the case for many professional money managers who have too many stocks in their portfolios. Very few have time to do deep dives on more than 20 companies, let alone maintain a superior understanding of all those portfolio holdings. Still, above-average investing is near impossible if you don’t do the deep fundamental work to invest with high conviction. In other words, having more than 20 positions in your portfolio makes you more of a tourist than an owner in most of your positions. Yet, an owner’s mindset is key to reap the benefits of compounding.

Selling compounders prematurely can be a life-altering mistake. Typically, a few top-performing investments will contribute the vast majority of your returns. In fact, it’s a common theme among the world’s greatest investors that a few winners have carried their entire portfolio. For example, Charlie Munger acknowledges having made almost all his money from a few big winners. The same is true for Benjamin Graham, Peter Lynch, Philip Fisher, Warren Buffett, and many other great investors.

The only time you should consider selling a compounder is when it stops being a great business, the position becomes too large in your portfolio if the company becomes wildly overvalued (trading at a premium to your most optimistic outlook) or cash is needed to take advantage of a superior opportunity. Otherwise, there is no need to reap the gains in compounders as these are companies that increase steadily in value – stocks to ‘buy low and let grow’.

Finally, only a handful of your positions need to be winners if you own enough compounders. It is easy to forget, but this is an asymmetric game: you can only lose 1x your investment, but some picks can 10x or even 100x if you have the conviction to hold long enough. Yet, the nature of compounding might give you the impression that getting an early entry is the only way to benefit from it. But even if you catch the compounding train late, it can still get you to your destination as long as you avoid the losers that cause permanent loss of capital.

What Makes a CompounderCompounders are companies that have strong competitive advantages and attractive internal and external reinvestment opportunities, including potential acquisitions. As such they have long growth runways and demonstrable track records of generating sustainable high returns on capital at a mid-teens annualized return or better. Also, these companies are managed by executive teams who have displayed a strong talent for creating value for both their customers and shareholders. Yet, this is a relatively rare combination, of course.

Most of the time these high-quality companies are too expensive, but they account for the vast majority of the stock market’s long-term returns. Trying to invest in compounders purely on an analysis of value is more likely to result in missed opportunities. Consequently, you should be ready to invest in compounders at reasonable prices (i.e. our Base Case fair value) and then remain patient as the stock performance roughly tracks the return on equity over time. Philip Fisher once said, “If the job has been correctly done when a common stock is purchased, the time to sell is almost never.”

Compounders are above all quality companies. To identify a compounder, at least one of the three categories (People, Business, Financials) in our proprietary company quality rating system must score a 5, whereas none can score below 4.

Moreover, you should not regard the short-term performance of a compounder as important as these are likely to be multi-year positions in your portfolio. Instead, you should base your decisions for these stocks on the rate of return that you assess an investment will earn over the next three to five years by being highly aware of any optionality in the business model or growth strategy. The latter means that the growth outlook is hard to intelligently incorporate in a DCF-model, which explains why you should not be too stingy on price. Moreover, when you buy these stocks, ask yourself if you would buy the whole company.

Björn Fahlén